Alcoholics Anonymous

How AA invisibly built the most influential decentralized society in world history

This is part one in a series about societies—rather than businesses or governments—that have made a meaningful impact on the world. Read part two here, and the series intro here.

The OG decentralized society isn’t what you’d think. It’s not onchain, it’s not DAO-managed, it’s not even founded in the 21st century. Instead this society was founded in 1935, in Akron, Ohio, quietly and without fanfare, by a couple of drunks who found a way forward for themselves.

That decentralized society is Alcoholics Anonymous. And its story is super instructive for startup society founders today, in prescient and unexpected ways.

But first, some context.

I posted this on Twitter recently (which Balaji himself actually liked):

The more I thought about it, I figured I could probably write this perfectly fine myself. So, below is a quick history of AA’s most important and instructive moments, followed by its most useful lessons for startup society founders and builders.

Darkest Before The Dawn

Before AA’s founding in 1935, American society literally didn’t know what to do with people who couldn’t stop drinking. Common "treatments" and punishments included:

Moral and Penal Approaches: Many alcoholics were relegated to city "drunk tanks," "cells" in "foul wards" of public hospitals, and the back wards of aging "insane asylums"

Medical Treatments: "Purge and puke" treatments using barbiturates and belladonna were common for those who could afford psychiatrists or hospitals, with long-term asylum treatment as another option for wealthier individuals

Aversion Therapy: In the 1930s, some doctors attempted to create disgust toward alcohol by adding emetic agents to alcoholic beverages or pairing them with alcohol consumption

Psychostimulant Approach: Some doctors administered amphetamines to alcoholic patients, believing it would create a feeling of well-being and reduce the desire to drink

Private Sanatoria: Wealthy alcoholics could seek discrete detoxification in private facilities known as "jitter joints," "jag farms," or "dip shops"

Inebriate Homes and Permanent Asylums: These institutions were common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries but largely collapsed between 1910 and 1925

In rarer cases, lobotomies were performed between the early 1930’s and late 1950’s

Then, in 1935: Enter AA.

No more forced asylums. No more aversion therapy. AA wanted to solve alcoholism, at a time when alcoholism was a critical social blight. It wasn’t a temperance movement that said others needed to stop drinking. Rather it was about solving the question of how to stop drinking yourself, if you know it’s devastating your life yet you can’t seem to quit.

The Usefulness of a Question

The key thing to know is that, at the start, AA was essentially a society formed around a question – how does one stop drinking? – rather than a commandment.

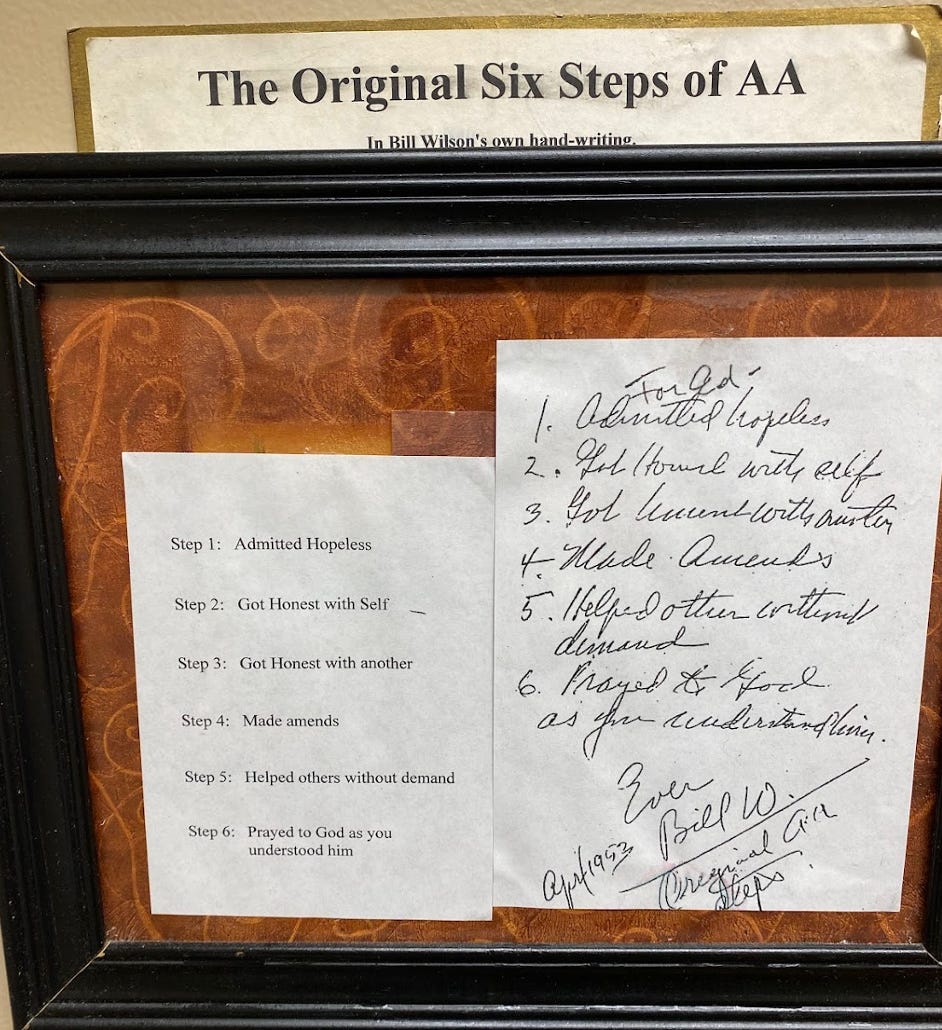

There was an inkling of a solution animated by the founders’ personal experience with a spiritual approach to solving alcoholism, originally introduced by the Oxford Group. This approach became the basis of the Twelve Steps that AA’s famous for.

But mostly their intent at the time was to go forward from that start to inquire deeper together about how one actually quits drinking for good.

For Balaji students, it’s worth noting this is one key difference between the most successful decentralized society in existence versus Balaji’s formulation of what’s necessary for a decentralized society. Of course you can manipulate AA’s actual ethos into a One Commandment of “don’t drink” – but the interesting thing about the earliest days of AA was that it mostly wasn’t working to help people quit drinking. “Don’t drink” wasn’t its commandment – it was its chief question.

On that note, co-founder Bill Wilson himself eventually comments in a letter that his work helping drunks in NYC (where he was a longtime resident as a former independent research analyst on Wall Street) was way less effective than the work happening in Ohio. But the NYC and Ohio contingents kept comparing notes, kept asking questions, and kept iterating their way toward recommendations that eventually would begin working for these desperate alcoholics.

So from these beginnings of failure, they evolved their way, over years, toward some semblance of a strategy that worked for a few people, then more, then even more, regardless of how bad their drinking situation was.

Groups began springing up across the nation as a result of their recruitment of drunks to join the community. And eventually three things occurred that shaped the growth of the nascent society in profound ways (that ultimately rippled into American history):

1. The creation of the Big Book

It occurred to co-founder Bill Wilson in 1939 (four years after founding AA) that a book would be a useful way to synthesize the previously-oral-tradition learnings and lessons of the community into a widely-distributable form. The problem was, they didn’t have any money to publish physical copies of the book.

So the former Wall Street guy came up with a novel way to finance the venture: they issued stock, at $25/share, in a new company they formed, called Works Publishing. They sold $5,000 worth of stock in 1939, which would’ve been equivalent to approximately $113,486.69 in 2025 terms.

The effects of the publication of the Big Book (as it came to become known among insiders) were profound. The book became one of the best-selling books of all time, with over 30 million copies in print. Time Magazine and the Library of Congress honored it as one of the most important American books of all time. In 2012, the Library of Congress designated it as one of 88 "Books that Shaped America." And the book has been translated into dozens of languages, allowing AA's message to spread internationally.

2. The publication of the Saturday Evening Post article

As the story goes, a journalist with the Saturday Evening Post (then one of the most popular publications in America) was deputized to write a hit piece about the fringe group claiming to help alcoholics. As part of his dutiful research, he attended an open AA meeting, and was surprised at what he encountered, so surprised he pulled a 180 on his piece’s original direction. He ended up writing a glowing account of Alcoholics Anonymous in the Saturday Evening Post.

The article was published on March 1, 1941, and was titled "Alcoholics Anonymous: Freed Slaves of Drink, Now They Free Others." The article became a major turning point in AA's history, with three big effects:

It caused AA membership to skyrocket from 2,000 to 8,000 within a year of its publication

The AA office in New York was flooded with 6,000 inquiries from alcoholics and their families seeking help

It sparked the first great surge of interest in AA, leading to exponential growth of the organization

This article basically introduced AA to a national audience, transforming it from an obscure self-help group into a widely recognized American institution.

3. The eventual decentralization of AA from a central coordinating office to a decentralized model of governance

Prior to 1955, AA’s shape, governance, and direction was basically led by Bill Wilson out of the New York office of AA, with a nonstop flurry of letters to group participants and leaders, essays in their community publication (“The Grapevine”), and occasional national gatherings.

But Bill Wilson wanted a decentralized governance model, rather than a centralized one, for AA. And it took twenty years of centralized governance to refine the organization’s steps and traditions to the point where he felt it could sustain its own leadership.

Here's eight ways this decentralization became meaningful for the longevity of AA, but the key one to note as hyper-relevant for today is this: “Long-term sustainability: By distributing power and responsibility, Bill W. ensured that AA could continue to function effectively beyond the lifetime of its founders.”

So in 1955 Bill Wilson gave administrative power back to the members of AA at the St. Louis Convention, a national conference for AA. This event is often referred to as AA’s "coming of age" when Bill W. released the Fellowship into maturity. (For anyone curious, the speech in which Bill W. outlined this transfer of power can be found in "The A.A. Service Manual combined with Twelve Concepts for World Service." Specifically, it's included in Appendix A of this manual).

This decision was a crucial stepping-stone for how there’s now 123,000 AA meetings crisscrossing the globe today.

Lessons For Society Founders/Builders

So far this has been a bit of a history lesson. But for founders and builders of startup societies, what are the biggest takeaways from the AA story? What’s maximally useful to extract from their work that could shape the next generation of beneficial societies helping humanity against seemingly intractable problems?

Obsession is table stakes

Against Bill Wilson’s own wishes (he preferred business success, which kept eluding him, rather than founding AA), the early AA members convinced him to forgo getting another Wall Street job, to instead dedicate his time to nurturing the new community he created.

At one point he and his wife lost their longtime home, and lived on the generosity of others for two years. They endured legitimate destitution in order to get Alcoholics Anonymous off the ground. And Bill lived and breathed AA for decades before decentralizing its governance.

The lesson is, obsession with the work is probably table stakes for making a meaningful dent in the world through a new society.

Tackle an insane problem

This one’s simple: let others try to solve the marginal problems. Work instead on enormous problems, civilizationally-large problems, problems that would necessitate a community achievement like AA to even begin solving them—but which energize the effort with purpose and significance beyond its inevitable humble beginnings.

Recall that alcoholics were getting lobotomized around the time AA was founded. What’s an equivalently “we have no idea what the fuck we’re doing” version of a problem today? Consider building a startup society around it.

Societies can research, not just command (One Commandment vs. One Question)

Balaji describes his imperative for One Commandment like this in The Network State:

“But we do think you can come up with one commandment. One new moral premise. Just one specific issue where the history and science has convinced you that the establishment is wanting. And where you feel confident making your case in articles, videos, books, and presentations. These presentations are similar to startup pitch decks. But as the founder of a startup society, you aren’t a technology entrepreneur telling investors why this new innovation is better, faster, and cheaper. You are a moral entrepreneur telling potential future citizens about a better way of life, about a single thing that the broader world has gotten wrong that your community is setting right.” pg. 137

But this assumes you have a definitive “single thing that the broader world has gotten wrong.” It also assumes you have a definitive way “your community is setting [it] right.”

This is probably well and good for many types of startup societies. But maybe for the most intractable problems, the most knotty and difficult issues, what’s needed instead is a fierce commitment to learning, and learning together, comparing notes, trying new approaches.

One example of this from the AA story is Bill Wilson’s early curiosity about psychedelics as an aid to the process of recovery. His personal experiments with LSD had him describe his opinion like this in a letter to a confederate:

“Dear Father Ed, …The LSD business goes on apace. This material should be of some value [for those] who already have the faith… As for those who have no faith, it could act very much as my original experience at Towns did. It might bring the gift of faith. However I don’t believe that it has any miraculous property of transforming spiritually and emotionally sick people into healthy ones overnight. In affection, Bill”

These explorations were not early in the life of AA. In fact they were well after AA already had established a reputation for total sobriety among its members, such that many AA members felt betrayed by Bill Wilson’s suggestions that a substance (LSD) might offer relief from another substance (alcohol).

Yet Bill founded the thing – he remembered that the intent was a question, not a definitive answer, and he wanted to keep pushing the frontier of how to help drunks solve their drinking issue, whether it rhymed with their past efforts or not.

Forming a society around a question gives it vitality, keeps it generative, allows an ongoing conversation and elicits ongoing contributions from its members.

One Commandment isn’t enough – you need Traditions, too

AA is world famous for its Twelve Steps, but its secret genius is actually in its Twelve Traditions.

The Twelve Traditions were designed as the bumpers for the community (which was constantly conflicting in the early days about the best way things should be run). It became the rules of the society, the governance rules that shaped how it would show up in the world.

Here’s a link in case you’re curious what they sound like, but basically every historian of AA credits the Twelve Traditions for getting the society out of its awkward adolescent years and into the hyper-growth period that made it a household concept.

Societies need rules. Design distinct rules that are unique to your efforts and shape your community for cohesion and coordination.

As an aside, the tradition that keeps AA as a healthy society rather than a Berkshire -or Vatican-sized conglomerate is this one (and subsequently is my favorite for its wholesomeness):

“Problems of money, property, and authority may easily divert us from our primary spiritual aim. We think, therefore, that any considerable property of genuine use to A.A. should be separately incorporated and managed, thus dividing the material from the spiritual. An A.A. group, as such, should never go into business.”

If that one tradition didn’t exist, it’s likely AA would be one of the most expansive and important businesses on the planet.

Finance the storytelling

There’s a general concept from corporate finance that risk capital (i.e., equity) should be used to finance risky activities, whereas funds with a lesser cost of capital (i.e., debt) should be used to finance more predictable assets and operations.

I think there’s an analog here for the early days of a startup society, too.

Use risk capital to finance risky storytelling, distribution, and media. Who cares whether it’s immediately viral or not. Get the message out there. Find your people, and connect with those who align with what you’re doing.

With today’s crypto infrastructure perhaps the risk capital comes from an ICO (if regulation gets cleared up), or perhaps it’s traditional VC like Praxis did (disclosure: I’m an investor in Praxis). But wherever the original risk capital come from, don’t underinvest in narrative, storytelling, distribution.

Legacy media had a much stronger monopoly in 1941 than today, but regardless, find the channels your ideal community members pay attention to – legacy or not – and risk the time and capital necessary to earn their involvement in what you’re building.

Create your modern version of the Big Book (whatever media form makes most sense). And find your Saturday Evening Post (whether it’s a publication or a podcast, or something in between) and let the uniqueness of your core purpose be heard.

Centralize governance until you’re ready

One of the difficulties with deductive ethical thinking is that it’s not always clear whether an expression of a principle makes pragmatic sense. One of the key ways this shows up is crypto’s historical preoccupation with decentralization as a de facto always and forever and in every situation right answer for how a system should be structured (both technically and in terms of governance).

The awkward reality of crypto’s past five years is that, pragmatically, centralization is much more effective at driving forward a particular vision – hence the common refrain of progressive decentralization, of “we’ll get there eventually” (which, let me be clear, I’m not knocking whatsoever).

This reality gets reiterated by the AA story. Beyond whatever org-chart controls the multisig, the truth is that instantiating a society ex nihilo requires leadership, guidance, coordination, that centralization enables dramatically better than decentralization. I’m enthusiastic about new hybrid models that allow new forms of coordination enabled by crypto. But if it comes at the expense of the ability to legitimately coordinate – in a way that even a skeptic would recognize as true coordination – then I’m prone to say follow the AA example (recall they decentralized only after 20 years of hyper-involved leadership by Bill Wilson).

Conclusion

The core of AA is a mystic tradition predicated on the belief that God will help you get sober. This is, on its face, for many people, inherently insane.

Yet AA has been the frontline of recovery for millions across the world for decades now, with Bill Wilson heralded by Time Magazine as one of the most influential people of the 20th century.

My whole thing in this piece is that more people should pay attention to AA’s founding and growth. If such an apparently-crazy notion can be at the center of such a successful society, surely less esoteric ideas can flourish too. But beyond that, if you’re building a startup society, I hope this essay helps encourage you.

The most important startup society in the world (well beyond Network State scale, if it weren’t for that tradition preventing “going into business”) started amidst much difficulty and almost didn’t make it at different points. So there’s hope and solace that others have built societies that have improved the lives of millions around the world, despite not really knowing what they were doing for at least part of their existence.

And the encouragement would be this too: maybe the 21st century is waiting for your push against an equally-cunning, equally-baffling, equally-powerful problem as alcoholism. If you really thought about it, what could a society solve that an individual couldn’t? I suspect this is one of the most important questions any prospective founder could be asking themselves here at the start of 2025.

If you think you’ve got an addiction issue, feel free to reach out – I’d be happy to chat with you about it, not as an expert but as a peer.

If you’re curious for a deep-dive on the AA story, the documentary titled “Bill W.” on Amazon is a great complement to what I’ve shared here.

If you want to chat more about AA’s history as it relates to startup societies, my DM’s are open (@tanner_gesek).

Thanks for reading.

Table of contents for The Society Builders series:

Alcoholics Anonymous: How AA invisibly built the most influential decentralized society in world history

The Clapham Circle: How 12 families in a London suburb abolished slavery

The Mondragon Corporation: A historical blueprint for cooperative capitalism (with a crypto lens)

MSCHF (aka Mischief, aka Miscellaneous Mischief): How to create a venture-backed art society that creates subversive culture

The Network School: Dispatch from the Malaysian ghost-city startup society (that bootstraps startup societies)

IBM: What their 1937 Song Book says about a bygone era of Corporations-as-Societies

The Society Builders: An Intermission—A quick essay for reflection, synthesis

The Fellowship: A cautionary tale of the secretive Washington DC "politico-religious" society

Rajneeshpuram: 4 lessons from the commune the U.S. destroyed

The NYC Italian Mafia: The promise and perils of "quick and quiet coordination"