This is the third and last essay in the Holy Fools series. Read part one and part two there. Realistically too, you can start with part two, and not miss too much from part one (as it’s quoted widely in part two).

1.

In his essay titled “Innovation takes magic, and that magic is gift culture,” writer Alex Danco (now a16z’s Editor at Large, as of two weeks ago) gives us some conceptual lego blocks that start to help make sense of this whole foolishness paradox. To recap, the paradox is: why does doing stuff that seems an awful lot like losing, somehow turn out to win?

The thrust of the essay’s first half is that the prosperity and productivity of Silicon Valley is essentially due to creating various gift cultures that solve certain coordination problems. His writing elsewhere asks the inverse question – why haven’t other Silicon Valleys emerged to become nearly as successful as San Francisco? – and in evaluating both the pro and contra versions, he lands on this central idea:

“Over the years of watching different parts of this world at work, I’m increasingly convinced that the innovation economy requires some sort of magic to actually work, and that magic is gift culture. Gift culture - which I’ll define loosely here as, “the social traditions within a community around gift exchange and reciprocity” - is load-bearing for creative builders, not just for feel-good reasons. Gift exchange does real economic work by elegantly solving coordination problems that would otherwise be prohibitively challenging.”

This is super interesting: we’ll unpack examples, but if you zoom out, Danco’s describing ways of showing up in the world that do “real economic work” but without the usual rational economic calculations. If you squint, it kind of looks like he’s describing a parallel ethical system—a parallel way of coordinating and collaborating—that works by very different rules but surprisingly still “wins,” even against who you’d expect to win if wearing a more rational hat.

Recall that Moloch is essentially game theoretic pressure to unhealthily compete, powered by “desire” (what you want) shaping ethics (how you operate), without people having the wisdom to opt-out or try something different. Moloch (or even “Moloch lite”) throws up normally “prohibitively challenging” coordination problems—yet Danco’s piece shines some light on at least a few ways to “elegantly [solve]” them.

Let’s make this clearer with some examples.

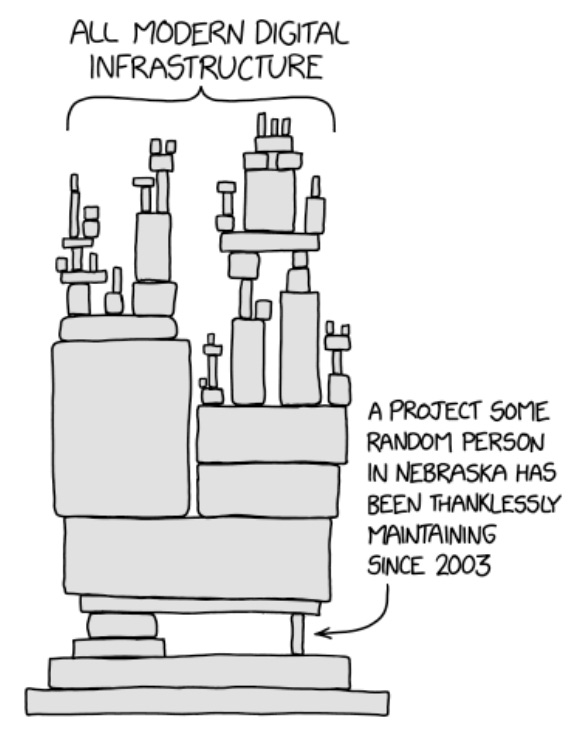

Consider open source software: that way of coordinating work is actually a third option beyond the usual two others for coordinating work (where “inside a company” or “among different companies selling each other goods and work” are the other two traditional options):

“The fascinating thing about open source (formerly “free software”, a much better name) is that it doesn’t just produce a free option for software staples; it often produces the best option in its category; sometimes shockingly better than any paid alternative. The question is, how can a bunch of people on a mailing list giving gifts to each other produce not only high-quality contributions, but high-quality synthesis of individual output into large-scale open source masterpieces? This is the interesting part. You can picture a community of dedicated nerds who take great pride in their craft, and great joy in repeatedly giving gifts to others, as a stable equilibrium. But the more interesting question is why it works collaboratively. What makes the sum greater than the individual parts?”

This is the right question! How does the “foolishness” of the free software movement end up converting the “gifts”—code contributions and synthesis—of a “community of dedicated nerds” into “large-scale open-source masterpieces”? If a venture-backed startup were going head-to-head against an open source project, most observers would expect the venture-backed startup to win. Yet that’s not necessarily the story of software’s history.

Or consider a different example, this time for early-stage investing rather than building. What if there were a “gift culture for capital” that ultimately finances Silicon Valley?

“Remember that the hard problem of financing innovation is the uncertainty around how many financing tranches you have until companies are graded on results as opposed to on potential. In any given financing, investors have to decide whether this is a “potential” round or a “results” round. The investors leading this year’s round cannot communicate with the people who’ll do next year’s round. If you could know with certainty which kind the next round would be, you could price today’s opportunity more straightforwardly. But we can’t time travel yet (until we beat thermodynamics), so the best we can do is send signals to the future, in the price and term structure we agree to today, about the gift being given today of grading the company on potential.

The gift-culture long game, which has been going on for decades in Silicon Valley, creates confidence that we can pass this “gift of grading on potential” forward, round after round. You can raise a Series A on the story of what the Series B story will be: “The appropriate thing would be for the next round to be priced at 40 at 150 post; can we count on people playing ball?” Everyone is gifting each other permission to not second-guess anything and go for the crazy outcome as opposed to the rationally optimal outcome.”

This “gift of grading on potential” permeates the early-stage investor ecosystem within Silicon Valley. But who starts this financing process? That question speaks to another requisite factor: a unique superposition that frees angel investors to put up the earliest funds to catalyze a project:

“From the outside, angel investing may look like it’s motivated simply by money. But there’s more to it than that. To insiders, it’s more about your role and reputation within the community than it is about the money. The real motivator isn’t greed, it’s social standing – just like a century ago, with the original Angels who financed Broadway shows. Angel investing is how you stay relevant. It’s how you keep getting invited to things. It’s how you matter. Angel investing isn’t about getting something, it’s about being someone. …

In an environment like this, angel investments are the ultimate flex. They’re the universally permissible bragging format: half “I saw this potential when none of you did” and half “I was invited to this deal and none of you were.” I don’t mean to say here that all angel investment is social posturing – some angel investors are among the kindest, most humble and helpful people I know. But the social returns to angel investment aren’t just a happy side effect. They’re often the main thing people are really after.

It’s also convenient that the investment return profile of angel investing for social status is way more attractive than angel investing for financial return. Angel investors’ money gets locked up for 5+ years (maybe even 10 years), so you face a significant illiquidity punishment relative to the S&P or even real estate. Second of all, your money gets massively diluted by follow-on capital. The more money a startup raises, the more you get washed out as a little guy who can’t defend pro rata.

But from a social returns perspective, you face neither of these problems. Not only are the social returns immediate, they also get reinforced by follow-on capital raises. That $50 million Series B for your favourite portfolio company might have washed you right off the cap table, but it’s an awesome achievement socially. As a bonus, even if the startup ultimately fails or you get recapped out of the picture, you still get a lot of the good will and recognition you were after. Even the downside scenario is pretty good, so long as you’re a good citizen about it.”

His conclusion drawn:

“This superposition of financial versus social returns, when considered in one investment, gets everybody in the round thinking in sync: “All right, we all know we’re here for an equity deal, but we’re going to follow social rules as though this were a gift exchange - I gift you capital; you gift me shares. We’re going to follow the rules of gift culture, and its insistence on accepting gifts and reciprocating them; and embrace the high-bandwidth communication channel for ‘figuring out what we’ve got here.’ (Described above.) And then at the end of the gift exchange, we’ll see if we have a path to doing a round that successfully gets us to the next round.”

So there’s two interesting concepts introduced in these examples: superpositions and gifts. And after a superposition of desire (social + financial) begins the process, a new gift-oriented ethic becomes possible that cascades across subsequent financing rounds (ultimately giving startups a real chance to actualize their potential). The result? Magic:

“Gift culture has sacred protocol: if you’re offered a gift, you must accept the gift, and you must reciprocate either in return or by paying it forward. If I offer you a gift, saying, “Here is all this information, promise and potential”, then by the rules of gift exchange, you are obligated to take it seriously, and you are obligated to offer some potential in return, for a window of time.

This frees (actually, compels) everybody in the gift exchange to embrace a measure of creative risk that, in normal circumstances, would signal “I am crazy”. There is a window of time in which different social rules apply, in which you have lots more room to move. You have until that window closes to “figure out what you have here”, at which point the gift exchange concludes, and normal economics reassert themselves. At that point, the deal or plan proposed goes through a conventional assessment of merit. And often it doesn’t pass, but sometimes it does, at way higher levels of ambition than would normally materialize. And that, my friends, is kind of magical. The gift exchange did real work; just like an enzyme does real work catalyzing a reaction.”

Similar to what we looked at in Holy Fools Part Two, it isn’t purely the domain of Moloch to solve coordination problems of “who goes first” in startup financing or “how do we build powerful software while loosely organized” in the open source community. There’s not a concrete structure of “from a God’s-eye-view and God’s-ability-to-coordinate, then ‘X’ would be ideal for everyone involved, but you aren’t God and can’t coordinate everyone, so ‘Y’ is what everyone has to settle for.” But they’re live examples representative of a broad class of coordination problems, of which Moloch is one type—so I believe we can still derive meaningful lessons from them, and better thinkers than I can port them over to understand Moloch-type problems.

Altogether I suspect Danco’s ideas constitute a useful analytical toolkit for not just Silicon Valley but lots of other “magical” phenomenon related to this concept of foolishness. The key question to be looking for among unusually generative communities (or instigated, if you’re creating one) is this:

“What unusual gifts, enabled by overlapping-yet-distinct motives, are unlocking cooperation that’s usually forbidden by the incentives of the game?”

That’s the generative fire—and the sensation of “this seems crazy” is the smoke, signaling that the fire is there. With that said, let’s use this new lens to look at not just an example of innovative economy like Silicon Valley, but rather an innovative society.

2.

In The Society Builders series, I started by looking at Alcoholics Anonymous, the most successful addiction recovery movement in the world. In that piece, I wrote this:

“As an aside, the tradition that keeps AA as a healthy society rather than a Berkshire -or Vatican-sized conglomerate is this one (and subsequently is my favorite for its wholesomeness):

‘Problems of money, property, and authority may easily divert us from our primary spiritual aim. We think, therefore, that any considerable property of genuine use to A.A. should be separately incorporated and managed, thus dividing the material from the spiritual. An A.A. group, as such, should never go into business.’

If that one tradition didn’t exist, it’s likely AA would be one of the most expansive and important businesses on the planet.”

As one example of many within the AA story, that decision could likely be seen, from a particular lens, as quite foolish. Why not “make yourself sustainable” by allowing AA groups to go into business?

Well, they say specifically why: because problems of money, property, and authority may easily divert them from their primary spiritual aim. So their desire to remain uncorrupted by those particular problems results in a quirky ethic that ultimately prevents them from growing into one of the most successful businesses of all time.

That’s foolish, from one perspective: but only a perspective that ultimately values business success above any other type of measurement of value. In other words, AA’s leadership wasn’t building AA to get rich, they were building it to help people suffering from alcoholism. So by their “foolish” desire (to serve altruistically rather than get rich) they crafted a “foolish” society (something completely free, powered by volunteerism, i.e., gifts of time and energy) as their gift to the world. And their oft-remarked “missionary” step of Step Twelve speaks to their concurrent desire alongside being helpful, which is to grow.

So, AA created an unusual gift culture (free sponsorship, free meetings, freely-available Twelve Steps), enabled by twin desires to freely help and to grow (so as to help more people), unlocking a supportive community utterly fixated on helping people avoid alcoholic ruin.

3.

But let’s pause quickly. Does that description of AA feel a little slippery to you? It might, and that’s okay if so.

What I’ve come to find in thinking about these things is that, in discussions like this, it really truly matters how you frame things. Because “foolishness” is a tricky enough concept to pin down that it be descriptive of many things, even things potentially unlike each other. For example, what does free speech (a political “foolish” imperative) have to do with forgiveness amidst competitive contexts (a religious “foolish” imperative)? They’re very different ideas, yet can both be considered “foolish” (in the sense we’ve been using the term) depending on the context and narration added.

And it gets more complex. Here’s a few parameters that matter (out of certainly and innumerably more) for parsing what exactly’s going on with foolishness:

The definition of useful: ultimately we care about whether a type of foolishness is useful or not, but defining what usefulness means is actually pretty tricky. Recall Scott Alexander’s free speech example: would you define free speech as “useful”? It’s certainly changed the nature of the game when implemented, and certainly can be framed as a foolish decision for political leaders. But was it “useful”? Useful for who? Useful how, and for what?

Time: This essay’s subtitle is “How foolishness wins”—but at what point do you measure whether something’s “won” or not? 75 years (like Silicon Valley), 90 years (like Alcoholics Anonymous), or 2000 years (like Christianity)? Given a competitive atmosphere, winners and losers can shift all the time. It’s a mistake to describe something as having permanently won.

Do you choose the Big Concept to measure win/loss status or the Individual Players?: For example, Christianity “won” (as measured by global population %), yet many Christians have certainly “lost” (their lives, property, safety, etc.).

Ultimately what’s clear is that “useful” or “winning” are super fraught success criteria to bring into the analysis. Which makes this difficult to talk about, because we care about generative foolishness and not masochistic or intentional stupidity.

And there’s a narrative component to this conversation that makes it especially difficult to really nail down what useful foolishness is vs. isn’t. Take the above, for example: I described AA’s decision to cordon off going into business as “foolish.” That’s a narration, a judgment, a description, but is it a type of useful foolishness we’ve looked at in this series? AA’s eventual success might lead us to narrate/judge/describe it is as useful: but how would you know or predict early-on that that decision would prove useful? What we’re trying to do here is unpack that question better: how to know, earlier, that you’re onto something, even if it’s not fruitful for quite a long time. But that’s very difficult, and perhaps not possible.

So it's an extremely difficult question, especially given the rhetorical nature of it—being able to describe something a certain way doesn’t necessarily mean it is that way. Or, more directly, just because something seems foolish doesn’t mean it’s foolish in the sense we’re describing. Even dubbing what we’re talking about “foolishness” was an editorial choice of mine: I’d said it feels foolish because you’re knowingly resisting game theoretic forces to compete in predictable ways. Alex Danco has a line in an essay elsewhere about rightsizing his thinking to merely “a blog-post level of precision”—i.e., not a philosophical monograph. So, with blog-post level of precision here, yes, these considerations are important, and they’re worthwhile to consider—but we’ll simply note all’s not as cut-and-dried as we’d like, and digress from here.

4.

I’ve long-suspected that toggling and playing with the basic ingredients of Moloch (i.e., desire and ethics) enables wider degrees of freedom for unlocking new collective possibilities. You can either quit desiring the prize, or you can operate differently. As hinted at in Part Two, one type of living differently is this idea of foolishness: yet some ways of living differently (i.e., “foolishly”) are immensely productive (like gift cultures for software and capital), whereas other ways of living differently (“foolishly”) terminate upon themselves as unhelpful or unfruitful.

As we’ve seen, there’s two particular elements that Danco suggests might make foolishness generative rather than terminative: superpositions, and gifts.

In “Foucault’s Pendulum” Umberto Eco writes this:

“Fools are in great demand, especially on social occasions. They embarrass everyone but provide material for conversation. In their positive form, they become diplomats. Talking outside the glass when someone else blunders helps to change the subject. But fools don’t interest us, either. They’re never creative, their talent is all secondhand, so they don’t submit manuscripts to publishers. Fools don’t claim that cats bark, but they talk about cats when everyone else is talking about dogs. They offend all the rules of conversation, and when they really offend, they’re magnificent. It’s a dying breed, the embodiment of all the bourgeois virtues. What they really need is a Verdurin salon or even a chez Guer-mantes. Do you students still read such things?”

Ultimately to be a fool in our sense is to “talk about cats when everyone else is talking about dogs.” Which, limit it just to investing for a moment, as a metaphor: foolishness is a type of contrarianism, where you can almost think of “early but right” as the equivalent of “foolish but useful.” The inverse would be “early but wrong,” equivalent to “foolish but useless.” Time itself still defines the decision eventually: you only find out later whether your earliness was “right” or your foolishness “useful.” But to take contrarian action, there’s still an element of foolishness in play.

5.

At the end of Scott Alexander’s The Early Christian Strategy, he writes this:

“But even without endorsing the full strategy, there’s a vibe there that I really like. Whenever I discuss moral issues, people in the comments section here will do the whole post-Christian Nietzschean thing: “If you admit moral obligations to people who can’t pay you back, aren’t you just cucked? Aren’t you unilaterally surrendering in this memetic war we’re in, destined to be replaced by civilizations/ideologies with more continence in limiting their altruism to useful people bound in bilateral contracts? Who the heck cares if some foreigner or animal is suffering? Isn’t that just pathological, a proof that you don’t have the steely will that it takes to survive?”

I admit these people’s position makes rational sense. But on the deepest level, I don’t believe it. There was an old 2010s meme video about all the characters in all the comics and TV shows fighting, and in the end the one who came out on top was “Mr. Rogers, in a bloodstained sweater”. Human history is the cosmic version of that meme. After all the Vikings and steppe nomads and Spartans have had their way with each other, the leading ideology of the 21st century thus far appears to be a hyper-Christian bleeding-heart liberalism: COOPERATE-BOT in a bloodstained sweater. I don’t know why this keeps happening, but I wouldn’t count it out.”

This series has been my attempt to “[not] count it out”—to connect some dots a little more analytically than I’ve seen elsewhere. Ultimately I can’t pretend to have this sorted out into any kind of framework that enables prediction or certainty that something which feels present-day “foolish” might yield someday-fruitful results. I hope by connecting these conceptual building blocks, others out there brighter than myself might find interesting ways to render this line of thinking even more useful and predictive. But just like “early but right” is itself a superposition of countless emergent attributes in a complex system, I suspect “foolish but useful” is too.

But let’s try our hand at Scott Alexander’s question. Why, indeed, does “this [keep] happening”? I think it’s because superpositions enable people to do things they wouldn’t normally do when locked into single goals (e.g., JUST financial returns, vs. both social AND financial returns), and without context of the overlapping games newly-in-play, the new game can appear foolish to onlookers or participants. And gifts are an inherently foolish-looking version of coordination—they’re perhaps not understood super well by the average person, yet they do remarkable and probably understudied work.

Ultimately something seems to happen when there’s superpositions and gifts involved that suspends reality-as-usual—something magical, something that Christianity and Alcoholics Anonymous and Silicon Valley all seem to be beneficiaries of in idiosyncratic ways. Given the narrative nature of analyzing this stuff, it’s extremely tricky to nail down precisely what that magic consists of. I think it probably takes an insider’s eye, like Danco has for Silicon Valley, to really conceptualize what’s normally tacit and illegible (but can be put in terms of superpositions and gifts, if you wanted to).

The notion of foolishness we’ve been working with goes beyond the behavioral economists interest in predictable irrationality: it’s more about irrationality unlocking the usually-impossible, by a path of unpredictable irrationality (in a narrow scope) unlocking favorable outcomes (in a larger scope) for things we might desire (innovative economies like Silicon Valley, or innovative societies like early Christianity or Alcoholics Anonymous).

So about this conversation, we might echo Steve Jobs’ encouragement: “Stay hungry, stay foolish.” There’s much more to learn about how this all works, and I hope to continue learning over time how to become even more “foolish but useful.”

P.S. You may be asking why early Christianity wasn’t covered more here. Weren’t we going to answer how Christianity eluded Moloch’s pressure to compete in the usual known ways? I think we have, in fact—or, at least the puzzle pieces are there. Ultimately I wanted to make this series about the “magic” achieved by solving unusually knotty coordination problems via gifts and superpositions. But for anyone knowledgable about early Christianity, you can narrate some superpositions quite easily I believe: for example, “heavenly benefits” vs. “earthly benefits” (so to speak - e.g., Matthew 5)

And vis-a-vis eluding Moloch, the expectation for resurrection enabled a dramatically different desire for their lives purpose (thus freeing early Christians to live radically foolishly, with a multiplicity of ways of living as “people for others,” i.e., aiming to make their lives a gift). I also think Constantine making Christianity the default religion of Rome took it out of its “Boho Dance” earliest period that ultimately catalyzed it to becoming globally dominant on a long-enough timeline. See below for Boho Dance description by Tom Wolfe.

“Pick me pick me pick me pick me pick me pick me pick me … 0 damnable Uptown! By all means, deny it if asked!-what one knows, in one’s cheating heart, and what one says are two different things! So it was that the art mating ritual developed early in the century-in Paris, in Rome, in London, Berlin, Munich, Vienna, and, not too long afterward, in New York. As we’ve just seen, the ritual has two phases:

The Boho Dance, in which the artist shows his stuff within the circles, coteries, movements, isms, of the home neighborhood, bohemia itself, as if he doesn’t care about anything else; as if, in fact, he has a knife in his teeth against the fashionable world uptown.

The Consummation, in which culturati from that very same world, le monde, scout the various new movements and new artists of bohemia, select those who seem the most exciting, original, important, by whatever standards-and shower them with all the rewards of celebrity.” – Tom Wolfe, The Painted Word

This is some top notch work